Alipio Abada executed his will on 4 June 1932.

The laws in force at that time are the Civil Code of 1889 or the Old Civil Code, and Act No. 190 or the Code of Civil Procedure which governed the execution of wills before the enactment of the New Civil Code.

The matter in dispute in the present case is the attestation clause in the will of Abada. Section 618 of the Code of Civil Procedure, as amended by Act No. 2645, governs the form of the attestation clause of Abada’s will.

Requisites of a Will under the Code of Civil Procedure

Under Section 618 of the Code of Civil Procedure, the requisites of a will are the following:

- The will must be written in the language or dialect known by the testator;

- The will must be signed by the testator, or by the testator’s name written by some other person in his presence, and by his express direction;

- The will must be attested and subscribed by three or more credible witnesses in the presence of the testator and of each other;

- The testator or the person requested by him to write his name and the instrumental witnesses of the will must sign each and every page of the will on the left margin;

- The pages of the will must be numbered correlatively in letters placed on the upper part of each sheet;

- The attestation shall state the number of sheets or pages used, upon which the will is written, and the fact that the testator signed the will and every page of the will, or caused some other person to write his name, under his express direction, in the presence of three witnesses, and the witnesses witnessed and signed the will and all pages of the will in the presence of the testator and of each other.

2-3. On Acknowledgment Before a Notary Public and Language or Dialect Known to the Testator

Caponong-Noble asserts that the will of Abada does not indicate that it is written in a language or dialect known to the testator. Further, she maintains that the will is not acknowledged before a notary public. She cites in particular Articles 804 and 805 of the Old Civil Code, thus:

- Art. 804. Every will must be in writing and executed in a language or dialect known to the testator.

- Art. 806. Every will must be acknowledged before a notary public by the testator and the witnesses.

Caponong-Noble actually cited Articles 804 and 806 of the New Civil Code. Article 804 of the Old Civil Code is about the rights and obligations of administrators of the property of an absentee, while Article 806 of the Old Civil Code defines a legitime.

Articles 804 and 806 of the New Civil Code are new provisions. Article 804 of the New Civil Code is taken from Section 618 of the Code of Civil Procedure. Article 806 of the New Civil Code is taken from Article 685

However, the Code of Civil Procedure repealed Article 685 of the Old Civil Code. Under the Code of Civil Procedure, the intervention of a notary is not necessary in the execution of any will. Therefore, Abada’s will does not require acknowledgment before a notary public.

Caponong-Noble points out that nowhere in the will can one discern that Abada knew the Spanish language. She alleges that such defect is fatal and must result in the disallowance of the will. On this issue, the Court of Appeals held that the matter was not raised in the motion to dismiss, and that it is now too late to raise the issue on appeal. We agree with Caponong-Noble that the doctrine of estoppel does not apply in probate proceedings. In addition, the language used in the will is part of the requisites under Section 618 of the Code of Civil Procedure and the Court deems it proper to pass upon this issue.

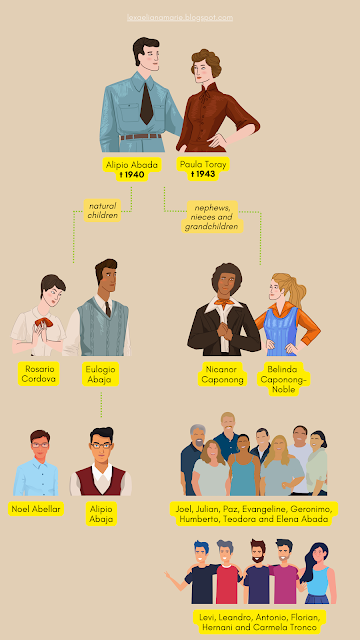

Nevertheless, Caponong-Noble’s contention must still fail. There is no statutory requirement to state in the will itself that the testator knew the language or dialect used in the will. This is a matter that a party may establish by proof aliunde. Caponong-Noble further argues that Alipio Abaja, in his testimony, has failed, among others, to show that Abada knew or understood the contents of the will and the Spanish language used in the will. However, Alipio Abaja testified that Abada used to gather Spanish-speaking people in their place. In these gatherings, Abada and his companions would talk in the Spanish language. This sufficiently proves that Abada speaks the Spanish language.

4. On the Attestation Clause of Abada’s Will

A scrutiny of Abada’s will shows that it has an attestation clause. The attestation clause of Abada’s will reads:

Suscrito y declarado por el testador Alipio Abada como su ultima voluntad y testamento en presencia de nosotros, habiendo tambien el testador firmado en nuestra presencia en el margen izquierdo de todas y cada una de las hojas del mismo. Y en testimonio de ello, cada uno de nosotros lo firmamos en presencia de nosotros y del testador al pie de este documento y en el margen izquierdo de todas y cada una de las dos hojas de que esta compuesto el mismo, las cuales estan paginadas correlativamente con las letras "UNO" y "DOS’ en la parte superior de la carrilla.

Translation: Subscribed and declared by the testator Alipio Abada as his last will and testament in our presence, with the testator also signing in our presence on the left margin of each and every page thereof. And as evidence of this, each one of us signs it in the presence of us and the testator at the bottom of this document and on the left margin of each and every one of the two pages that compose it, which are consecutively numbered with the letters 'ONE' and 'TWO' at the top of each page.

Caponong-Noble proceeds to point out several defects in the attestation clause. Caponong-Noble alleges that the attestation clause fails to state the number of pages on which the will is written.

The allegation has no merit. The phrase "en el margen izquierdo de todas y cada una de las dos hojas de que esta compuesto el mismo" which means "in the left margin of each and every one of the two pages consisting of the same" shows that the will consists of two pages. The pages are numbered correlatively with the letters "ONE" and "TWO" as can be gleaned from the phrase "las cuales estan paginadas correlativamente con las letras "UNO" y "DOS."

Caponong-Noble further alleges that the attestation clause fails to state expressly that the testator signed the will and its every page in the presence of three witnesses. She then faults the Court of Appeals for applying to the present case the rule on substantial compliance found in Article 809 of the New Civil Code.

The first sentence of the attestation clause reads: "Suscrito y declarado por el testador Alipio Abada como su ultima voluntad y testamento en presencia de nosotros, habiendo tambien el testador firmado en nuestra presencia en el margen izquierdo de todas y cada una de las hojas del mismo." The English translation is: "Subscribed and professed by the testator Alipio Abada as his last will and testament in our presence, the testator having also signed it in our presence on the left margin of each and every one of the pages of the same." The attestation clause clearly states that Abada signed the will and its every page in the presence of the witnesses.

However, Caponong-Noble is correct in saying that the attestation clause does not indicate the number of witnesses. On this point, the Court agrees with the appellate court in applying the rule on substantial compliance in determining the number of witnesses. While the attestation clause does not state the number of witnesses, a close inspection of the will shows that three witnesses signed it.

This Court has applied the rule on substantial compliance even before the effectivity of the New Civil Code.

An attestation clause is made for the purpose of preserving, in permanent form, a record of the facts attending the execution of the will, so that in case of failure of the memory of the subscribing witnesses, or other casualty, they may still be proved. A will, therefore, should not be rejected where its attestation clause serves the purpose of the law.

We rule to apply the liberal construction in the probate of Abada’s will. Abada’s will clearly shows four signatures: that of Abada and of three other persons. It is reasonable to conclude that there are three witnesses to the will. The question on the number of the witnesses is answered by an examination of the will itself and without the need for presentation of evidence aliunde.

The phrase "en presencia de nosotros" or "in our presence" coupled with the signatures appearing on the will itself and after the attestation clause could only mean that:

(1) Abada subscribed to and professed before the three witnesses that the document was his last will, and

(2) Abada signed the will and the left margin of each page of the will in the presence of these three witnesses.

Finally, Caponong-Noble alleges that the attestation clause does not expressly state the circumstances that the witnesses witnessed and signed the will and all its pages in the presence of the testator and of each other. This Court has ruled:

Precision of language in the drafting of an attestation clause is desirable. However, it is not imperative that a parrot-like copy of the words of the statute be made. It is sufficient if from the language employed it can reasonably be deduced that the attestation clause fulfills what the law expects of it.

The last part of the attestation clause states "en testimonio de ello, cada uno de nosotros lo firmamos en presencia de nosotros y del testador." In English, this means "in its witness, every one of us also signed in our presence and of the testator." This clearly shows that the attesting witnesses witnessed the signing of the will of the testator, and that each witness signed the will in the presence of one another and of the testator.

5. On Resorting to Evidence Aliunde in the Probate of the Will

The Court explained the extent and limits of the rule on liberal construction, thus:

The so-called liberal rule does not offer any puzzle or difficulty, nor does it open the door to serious consequences. The later decisions do tell us when and where to stop; they draw the dividing line with precision. They do not allow evidence aliunde to fill a void in any part of the document or supply missing details that should appear in the will itself. They only permit a probe into the will, an exploration within its confines, to ascertain its meaning or to determine the existence or absence of the requisite formalities of law. This clear, sharp limitation eliminates uncertainty and ought to banish any fear of dire results.